EV Myths

There are many myths about electric vehicles (EVs), many pushed heavily by interested parties and shared by those who wish to cling on to their old internal combustion engined vehicles (ICEVs). I want to explore some of those here.

Dispelling the EV Myths

EVs are built on the back of child labour

The amount of times I’ve seen people state, with anger, that EV batteries are built with lithium mined by children in places like the Democratic Republic of the Congo is quite staggering. These people frequently blame the abuses of these children completely on the EV industry.

The mines pictured in these arguments are, usually, not the mines linked with minerals for EVs at all, but simply mines that the creator has selected to push their agenda. That is however, largely irrelevant.

Lithium

The mineral lithium is the most significant one used in the production of batteries for EVs. The biggest source for lithium in the world is Australia, not Africa.

There is an abundant supply of lithium, from Australia, Chile and China. A significant proportion of the lithium is not mined, but instead is distilled or evaporated from brine water. It is a lengthy process, but involves absolutely no child labour.

The vast majority of the lithium, mined or evaporated, is actually not used in EV batteries, but in mobile phones, tablets and computers. In other words, almost without exception, those complaining about lithium mining are doing so on a device that requires lithium.

Cobalt

Another mineral that causes much consternation in anti-EV circles is cobalt.

There are valid concerns about cobalt mining in certain regions, most notably in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. However, as referred to in the text above, the vast majority of the cobalt mined actually goes into mobile phones, tablets and computers.

If you’re going to complain about the minerals being used in EVs, it would be hypocritical not to complain equally about their use in other electronic devices.

Change is coming

The EV industry, perhaps because of the criticism, has been active in trying to improve the ethical sourcing of minerals, driving change.

Moreover, these companies are beginning to move away from the use of cobalt. Tesla are actively reducing the level of cobalt used and there are other battery technologies that look to use no cobalt at all.

The meme above is yet another example of people deliberately misleading the target audience. The image is from a copper mine, not a lithium mine.

Batteries Don’t Last

There are lots of posts on social media claiming that EV batteries need to be replaced after five, or even three years.

Of course, this is complete nonsense.

The first EV I owned was a ten year old Nissan Leaf 24kW. You can read a mini review on the car elsewhere on my website.

I bought it when it was already ten years old, as an interim vehicle in between my old diesel 4x4 and the EV I now use as a private hire vehicle. As an early Leaf, it did not have the advancements of more modern EVs and so was more prone to suffering from depletion. After 10 years of life charge cycles, in its old home on Jersey, the battery had lost a third of its ‘health’. So, effectively, it was just a 16kW Leaf. I still used it to drive my girlfriend to and from work. I used it to go shopping in nearby towns and cities. And I used it to take my girlfriend for a hair appointment that was right on the edge of the car’s range.

It still worked.

I guess that the reason so many people are willing to believe bad things about EV batteries, is because they’re used to the batteries in their smart phones depleting and becoming virtually useless.

The thing is, the batteries in EVs, even the early ones, have active battery management. EVs charge in a much smarter fashion, only replenishing depleted cells, which distributes the load across many thousands of cells that make up the whole pack.

What about the guarantees

EVs come with extremely long guarantees, typically at least eight years and as much as 100,000 miles.

Car manufacturers would not offer such guarantees if they were not confident in the cars, or more importantly the batteries, being able to deliver.

The car manufacturers have delivered on the promises of the warranties, multiple times.

One example of this would be the Model S Tesla used by a Californian taxi business, which has so far covered over 400,000 miles. During that 643,738 km, the HV battery (the one that powers the car’s electric motors) was replaced twice. The first time was at 194,000 miles, which it covered in just over two years. The car had been repeatedly charged to 100% from a low state of charge, multiple times a day, against the advice from Tesla. And yet they still swapped the battery under the warranty. The battery degradation was just 6%; not too bad for a car that had done such mileage.

But, the second battery didn’t fare as well.

Tesla replaced the battery again after a further 130,000 miles, which the Model S had completed in a matter of months, This time the depletion was worse, at 22%. The diagnostic checks showed there was an issue and so Tesla replaced the HV battery again and did some firmware updates to try and ensure better performance going forward.

EVs Are A Fire Risk

Yet another myth that I see on a regular basis, is that EVs are more likely to catch fire.

In actual fact, there is an element of truth to the claim, but to suggest that EVs catch fire more often is blatantly misleading.

When looking at the number of vehicle fires per 100,000 units, hybrid vehicles (those with both an internal combustion engine and an electric motor) have the most fires. I’ve looked at statistics from both America and Australia, both of which make it clear.

Fully electric vehicles are recognised as being far less likely than both hybrids and petrol or diesel cars to catch fire. For EVs, it is ‘just’ 25.1 fires per 100,000 sales and that compares to 3,474 hybrid fires and 1,529 ICE fires per 100,000 sales respectively.

The lithium batteries in EVs result in different types of fire characteristics to those seen in cars with petrol or diesel engines. The EV batteries produce poisonous fluoride gases when on fire, but take much longer to develop. For the driver and any passengers, this means they are far more likely to have time to escape the fire before things really take hold.

However, EV fires do burn for a long time, and are harder to put out. The thing is that pure ICE cars are over 60 times more likely to catch fire in the first place an hybrids are over 138 times more likely to go up in flames.

So, EVs aren’t the big risk

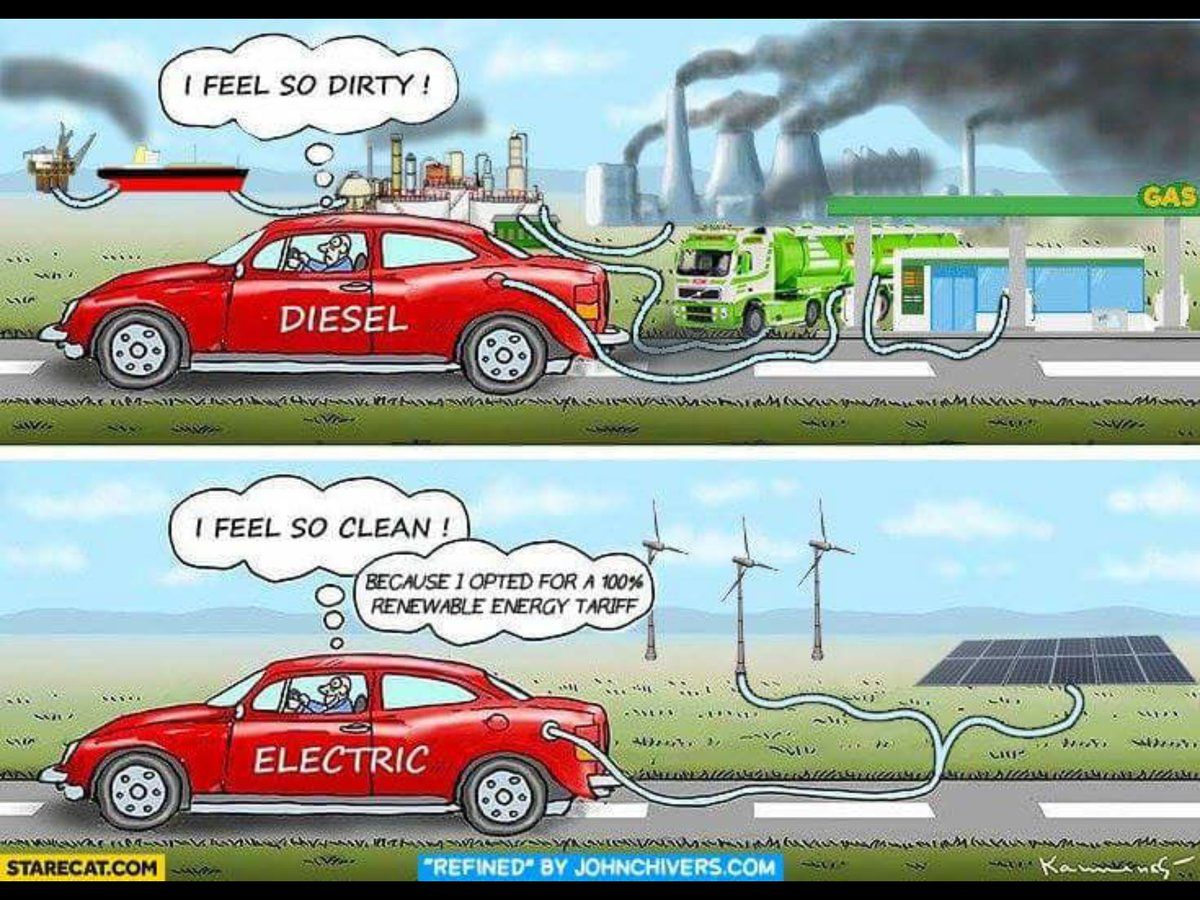

EVs Are Just as Polluting as ICE Cars

There are frequent claims that electric vehicles are as polluting, or even more polluting, as the petrol and diesel cars they are going to replace.

Some of this is based upon the fact that EVs do indeed have a greater environmental impact during the construction phase. The European Environment Agency (EEA) has stated that emissions from electric vehicle production are higher than those created by building an internal combustion-engined vehicle. One of the studies indicated that CO2 emissions from electric car production are almost 60% higher than those for the production of ICE vehicles.

This is largely because of the battery manufacturing process, and attempts are being made to improve this, bot in terms of the minerals used and the methods of obtaining them, and the increased use of renewable energies. Volkswagen, as an example, claim that their EVs are built in a carbon neutral manner and more manufacturers are bound to follow the same path.

However, once an electric vehicle begins its life on the roads, the bulk of its emissions have already been expended. On the other hand, for cars and other vehicles with combustion engines, a long period of tailpipe emissions is just beginning. And it’s not just those tailpipe emissions. It’s the whole process of getting the fuel to the filling station in the first place.

The majority of the electricity generated in the UK (and in the US, amongst others) is from renewable sources, meaning the EVs are primarily getting charged from renewable sources, rather than fossil fuel plants. Some public charging hubs have their own sustainable energy sourcing facilities, such as solar, and many homeowners also have solar power to help with the generation of ‘free’ electricity for their EVs.

I hope to be able to ad a video here shortly, trying to put into some context the pollution from the use of ICE cars that many people seem to be unaware of, or simply haven’t thought about.

EVs Don’t Have Sufficient Range

A common fear about the switch to driving a electric car is the one about range.

In the early days, with the 24kW Nissan Leaf, there may have been some justification for worrying about it; at least for some people. The early cars had a supp;owed range of 109 miles, but in real world driving this would have been more likely to have been just 90 miles. Moreover, if people drove aggressively, this would come down further; just as it does with petrol and diesel cars. And, back then, the charging network was not very expansive.

I recall having a seven day test drive in an early Tekna model and trying to charge in various places. We charged at Beaulieu Motor Museum (obtaining a charge card from reception), and then, after driving around a bit, tried charging in Lymington. We’d found reference to a charger in a council car park, but it was just some three pin sockets, so was painfully slow. On our way home, we stopped at Rownhams services on the M27, where there was one rapid charger. There was another Leaf charging and we chatted to the driver. He was a big fan of his Leaf and covered lots of miles, but he carried a generator in his boot as an emergency measure - I think he said he hadn’t needed to actually use it.

But, and it’s a big but, the average car in the UK travels just 142 miles in a week. So, even then, a range of about 100 miles should not have presented too much of an issue for most. This was especially the case as Nissan (back then) would install a free charger at your home when you bought a new Leaf. In fact, they told us they would also fit one at another address of our choosing (with the home owners permission), so if there was somewhere you regularly went, they’d put a charger there too! And, they provided free ICE car hire for two weeks a year for those occasions where you felt your battery electric vehicle wasn’t going to be suitable.

I owned a 2012 Leaf 24kW for six months and, with a depleted battery, it only had a range of about 56 miles. However, with the expansion of the charging network, I actually managed to use it quite effectively.

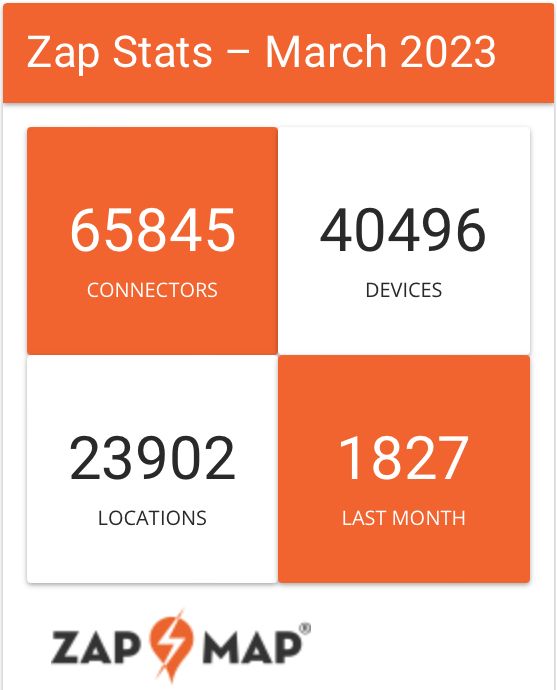

Nowadays, most electric cars have better range and the charging network is significant.

There are, as at February 2023, 8,356 petrol filling stations in the UK and the latest figures show there are 23,902 public charging locations, serving a fraction of the number of cars. Moreover, the majority of EV drivers have some capacity for home charging and many also have the ability to charge at their place of work.

The suggestion that EVs don’t have sufficient range is simply untrue.

Some people will say that need to be able to drive 400+ miles without stopping, which they can’t do with an EV. I’d suggest that, in all but a few extreme cases, they can’t do it in a petrol or diesel car either. Whilst our speed limits on motorways and dual carrriageways may be 70 mph, the actual average speed driven is slower. Even just the driving speed on the motorway is, on average, less than 70 mph, without the other roads and junctions bring the average speed down. If we’re being overly optimistic and saying we will achieve an average speed of 50 mph, driving 400 miles will take eight hours. Aside from the fact that the Highway Code and motoring organisations recommend a break every two hours on a long journey, most people with need to stop to use the toilet, eat and drink on such a long journey.

Typically, on a longer journey in my EV, I need to stop to stretch my legs, use the toilet and grab a coffee long before I need to stop for a charge. In recent cases, by the time I’ve had that coffee, my car is back up to 80-90% charge; more than enough to complete my journey. I haven’t had to wait for a charge and I haven’t had to, after my coffee, drive to the neighbouring fuel station to top up with petrol or diesel.

It’s worth thinking back to the case of the Tesla that had done 400,000 miles in just three years. That might be the extreme, but it hardly supports the argument that electric vehicles can’t cover the miles.

Other Sources of Information

There is an awful lot of useful information available online. There are too many sources of good information out there for me to provide them all here, so I’ll leave it (for the moment) with just these two.

The UK government have provided information on their website, trying to address the huge amount of misinformation about electric vehicles. But they’re not alone. Click the screenshot of the government website above to see their debunking of anti-EV myths.

Click on the screenshot from the Fully Charged show to be whisked across to their site and the wealth of information available.